Boston in American History

Since we're from the west we're more familiar with western

history -- the Oregon Trail (1841), the California gold rush (1849) and

the shoot-out at the O.K. corral (1892). In the west we traveled

through towns with buildings dating in the early 1900's and once in awhile

in the late 1800's. Compared to the East Coast, western accomplishments

and "historic" sites seem recent to us now.

|

We've been studying American History with the kids ever

since we started traveling. We've learned that the patriots of Boston were

the ones that sparked the Revolutionary War, so we were anxious to see

the sites here.

This is the Old South Meeting House in Boston, built in

1729 as a Congregational Church. Both the exterior and interior have

been beautifully preserved. The pews have been marked with the names

of it's regular parishioners, (General George Washington among them).

As it was the largest church in Boston, it also served

as the town's meeting hall. It was here, on December 16, 1773, that

a meeting was held to discuss the British tax on tea and the continuing

problems the Colonists were having with the Mother Country.

During the Revolutionary War, the British took over and

occupied Boston. To insult the locals, the British tore out the lower

seating area and turned the Old South Meeting House into a horse stable

and riding arena, with view seating on the sides and balcony. After

the war, the Boston residents restored the hall to a church and meeting

hall. |

I'll bet most of you are like me -- I can tell you

that "American History" is a required class in high school. If you

read the questions at the end of the chapter in the text books you can

get most of the answers for homework and the tests. I focused on

math, science, electronics, computing and extra curricular topics that

I won't go into here, so History to me was really a lot of "sound bytes"

-- you know; "Columbus", "the Pilgrims", "the Revolutionary War", "the

Cumberland Gap", "the Louisiana Purchase", "the Civil War", "the Oregon

Trail", "the Tennessee Valley Authority" and on and on -- a bunch of familiar

sounding words with no depth.

As we drive, Cheryl often reads history to the kids.

We have a thirteen volume set entitled "The Making of US", by Joy Hakim.

It's written more as stories rather than a textbook. (Wow, what a concept

-- stories that teach!) We are getting the in-depth story prior to

visiting the historic places we read about. It makes places like

Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., etc. so much more meaningful.

|

So, we've become real "history nerds" -- now we ponder

very unusual things, like:

-

How communication occurred between Boston and Philadelphia

with limited roads, if any, and treacherous seas.

-

We find it interesting that Benjamin Franklin and Samuel

Adams grew up together in Boston. Sam was instrumental in firing

up the crowd to start the Revolution, (but did not own a brewery).

Ben Franklin was a statesman and diplomat that ended up in Philadelphia

but was just as instrumental in the Revolution.

-

How did the British and the Colonists, in the middle of the

war, stay divided by a river for weeks?

|

First I thought I'd try to capture the details that make

the American Revolution so interesting -- the forces and human motivation

that brought about a remarkable government that had never been tried in

the civilized world. But guess what? It'd take longer than

I have to write and longer than you have to read. Besides, reading

about it without gaining the understanding obtained by a personal visit

just won't create the same experience.

The picture above is The State House. It is the

original home of the King's appointed British Governor who oversaw the

Colony of Massachusetts. It was in front of this building that five

Colonists were shot by British soldiers in what is known as "The Boston

Massacre". The "Massacre" sounds like it started out a lot like the

World Trade talks in the Seattle last year, (only no shots were fired in

Seattle). It happened five years before the start of the Revolutionary

War. A crowd became unruly and harassed a small group of British

soldiers. A shot was fired, (no one knows from who), and that started

a skirmish in which five Colonists died. Regardless of who was right

or wrong, it was a step toward uniting the Colonists against the British.

By using a lot of press and exaggeration, Sam Adams used this event to

paint a brutal picture of the British soldiers and the Crown's rule.

|

Bunker Hill Memorial

Ranger Gagnon at Bunker Hill National Historic Site provided

the best talk we've ever heard at a National Park. He described how

tensions led to the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party and the Battle

at Lexington and Concord.

After the Battle at Lexington and Concord the British

closed the Boston Harbor and occupied the peninsula, (which was the entire

city of Boston). Since no fort or barracks existed in Boston, one

or two British soldiers moved in with each Boston household. (That'd

be like one IRS agent and one FBI agent moving in and living in your house

with you and your family).

|

|

Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill across the river to the north

and another hill across the water to the south, would provide an advantage

to the British if they occupied them. As Ranger Gagnon put it, with

the high point advantage they could move from both the South and the North

and wipe out the "Colonial rats nest" to the east in Concord.

Well, to continue simplifying this story, word got to

Concord that the British were planning to move on the hills. So the

Colonists organized as best they could. Quietly, in the middle of

the night, they moved on to the hill in Boston. They dug quietly through

the night using shovels, sticks and even their hands to make an earthen

battle line. When dawn came, both the Colonists and British could

not believe their eyes. The Colonists saw that they set up too close

to shore and within reach of British naval cannons. The British saw

that there was suddenly a Colonial fortification looking down on them.

It took the whole morning for the British to rally together so by noon

the Colonists had further fortified their position.

|

Here is a diorama of the Bunker Hill Battle. The

Colonist are seen in the background, the British in the foreground.

The earthen birm and fence runs toward the river with half of it shown

here. The British had assumed that the Colonists were no match for the

world's most powerful military force.

"Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes" was

the command given the Colonists as the British charged. They had

to make every shot count. Their supply of gunpowder was small and

they only had muskets they had brought from home. After hours of

fighting, the Colonists ran out of gunpowder, retreated and ultimately

lost the hill. |

Though they lost the battle, the causalities were shocking

-- one to four in favor of the Colonists. The British had lost a

third of their entire force in the colonies. The British ego was

devastated by their huge losses. This battle displayed to the Colonists

that battling the British was possible.

|

Breeds Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was actually fought on Breeds Hill,

(which is just in front of Bunker Hill). The Colonists planned to set up

on Bunker Hill, but in the dark of the night they traveled past Bunker

Hill to Breeds Hill. This hill looked like a better spot to look

down on Boston.

|

This celebrated battle that the Colonists fought and lost

was in the wrong place. It was however, the first large battle of

the Revolutionary War and is known today as "the shot heard around the

world".

| Here's a monument to Paul Revere and the famous steeple

of the Old North Church in the background. Well, everyone has heard

of Paul Revere and his famous ride, but we never hear about Billy Dawes

and Dr. Samuel Prescott. All three of the men set out on the night

of April 17, 1775 to warn the Colonists at Concord that the British were

coming. |

|

The British were planning to capture the cache of Colonial

arms and gunpowder stored in Concord and to locate Sam Adams and John Hancock

who were considered high treasonists by the British. The events of

that evening provide a great story and all three men carried out their

roles successfully to warn Concord.

|

But then why is this simple house, the house of Paul

Revere, preserved today and not Billy Dawes and Dr. Prescott's? Well,

it wasn't until the Civil War that Paul Revere actually became famous.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was troubled in the mid-1800's when he could

see that the nation was be split apart by the threat of a civil war.

He had heard about a fellow named Paul Revere and his role in notifying

the Colonists at Concord. He was touched by the story and the way

in which the Colonists had pulled together to create our nation. |

He wrote the poem of Paul Revere's Ride in an effort to remind

us to stand together around the principles that formed our country.

So today Paul is famous and the others aren't. Paul was a silver

and coppersmith. Paul's descendants continue an interest in the family

business known today as Revereware.

|

There are several cemeteries in downtown Boston. As we

drive along the east coast, we notice many more small cemeteries, usually

in the side yards of neighborhood churches, than in the western states.

In some areas, especially near the coast, it seems like there's one every

other block. |

|

Walking through this cemetery is like reading a history

book. Many of the early Patriots are buried here. |

|

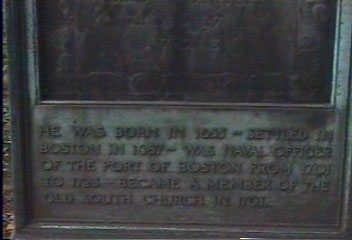

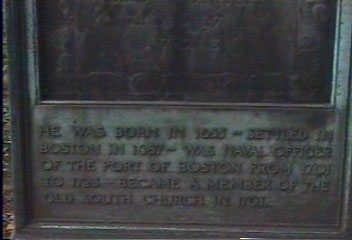

I was impressed with the dates and stories on many of

the tombstones. Here's just one example. Remember, the Pilgrims

landed in 1620 and the Revolutionary War started in the 1770's.

HE WAS BORN IN 1655 - SETTLED IN BOSTON IN 1687

- WAS NAVAL OFFICER OF THE FORT OF BOSTON FROM 1701 TO 1725 - BECAME A

MEMBER OF THE OLD SOUTH CHURCH IN 1721

|

Here's a few more people that are buried here.

(The words are from a tourist plaque).

James Otis, 1725-1783. Legal scholar and outspoken Stamp

Act critic. Of his fiery speeches John Adams stated, "American independence

was then and there born."

Victims of the Boston Massacre, 1770. Here lie the first

colonist killed by british troops.

Crispus Attucks, first to die, was of African and American Indian

descent.

Three signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Samuel Adams, 1772-1803: The "Grand Incendiary", powerful advocate

of independence.

Robert Treat Paine, 1731-1814; Prosecutor at the Boston Massacre

trial and Massachusetts' first Attorney General.

John Hancock, 1737-1793; First signer; Governor after independence.

Franklin Family Obelisk, Statesman, author and inventor

Benjamin Franklin was buried in Philadelphia in 1790.

Here lie his parents, his 16 siblings, and a relative of the same name.

"Mother Goose" According to popular legend, Elizabeth Goose

wrote the nursery rhymes printed in 1719 by her son-in-law. Her grave

is uncertain but members of her family are buried here.

Paul Revere, 1735 -1818. Silversmith and engraver. Rode

to Lexington to warn Hancock and Adams of the British advance. His

rolling mill made copper to cover the State House dome.

Samuel Seawall, 1652 1730. Chief Justice of the colony

(1718-1728); foe of slavery and the only judge of the Salem Witch Trials

to later denounce 19 death sentences.

Peter Faneuil, 1700 -1743, Faneuil Hall was a gift to Boston

from this wealthy merchant.

John Smibert (1688-1751), Fanueil Hall's designer, is also

buried in Granary, in an unmarked grave.

|

The U.S.S. Constitution, "Old Ironsides"

|

|

|

Mitch takes the helm. |

| Below on the cannon deck is an impressive array of firepower.

This ship is solid cannon from bow to stern. |

|

|

The Bell In Hand Tavern, 1795

America's Oldest (still operating) Tavern

According to the date, this tavern was not in business

at the time of the Revolutionary War, but it's been in operation for an

awful long time.

The local taverns were the places to discuss business

and politics. Since there was no postal service, (until Benjamin

Franklin started one), the mail was dropped off at the local tavern and

distributed there.

|

ã

copyright Nodland 1999-2020